Life is a little bit harder for the ones on the front-lines. If you are someone who is innovating on new stuff rather than imitating or refining existing ones, you’ll have more decisions on your hands, with much less information to make them. And unfortunately, one of the hardest of these critical decisions is, you’ve guessed it, settling on a price for your service or product. Doing this when entering a traditional market with established competitors might be relatively easy, especially if you are a stable player with well-defined practices. But what if you are trying to create a market instead of entering one? What if competitive pricing is out of the question? What’s left to help you decide what to charge people then?

Some people would say pricing is more art than science and that is true in a way. But it doesn’t mean it’s impossible to make it more sciency. Over the course of this article, that’s what we’ll try to do. By asking ourselves a few questions that will increasingly narrow our ranges, we will create a simplified pricing model together. Hopefully, by the end of it, there will be much less space for artistic license.

A Simple Pricing Model

It is the empty canvas with the grey background on the side. Yes, it’s a little too simple for the moment, but I heard good things about virtues of starting things and adding stuff to it should be easy enough. For starters, we can look for some hard boundaries for the values that we’re after. Limits that don’t make any sense to go beyond in any case. It would be a sensible starting point for our model, and calculating those should be quite simple with questions that have objective answers. From there, we could complicate things by getting more subjective as much as we wish.

Upper Limit

This is the reddish border that we shouldn’t cross. The one that would make people go “Screw that!” when we do. Some people approach this with profit margins in mind. That’s almost always a bad idea because people’s impression of a product and its costs to you mostly do not correlate. You can charge as much as your customers willing to pay and to have a meaningful sense of how much that is you need to ask yourself these two questions:

- How much money are you saving them? Selling anything, including ideas, most of the time is about the value proposition. You should know your product and what kind of benefits it provides better than anyone. Try to translate all that value into currency, so that it’s clear as day to anyone who considers buying. How much you are going to save on their operational costs, how much more efficient they are going to be, and how it will affect their bottom line in total? In the end, if a service costing you a thousand dollars to provide, helps your customers more than a million with their finances, you’ll see that you could easily charge a million, and people would prefer to pay you that than not.

- How much worth they are putting on the need: Sometimes the service you provide doesn’t save money but satiates needs like hunger, entertainment, social status, or combination of those. Research time, if that’s the case. You need to know your target market a little bit better. Try to find out how much money they are willing to spend on services that satisfy the same needs. Social status is a tricky one here because it could rise with your price. More you charge for a diamond, more dopamine for the people that have it weirdly.

That was easy. Unless you were considering giving money to your customers, we just limited the infinite possible answers to a finite set. That’s good!

Lower Limit

Now if only we knew where our lower border is standing too. That greenish one that we should definitely cross on average throughout our financial plan. The one that would make our investors go “Screw that!” when we don’t. For that, we have two fundamental questions to answer once again.

- What’s cost of your product to you? Sounds simple right? Although unfortunately, this isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. Of course, we have the initial costs to create the thing. But then we also have the ongoing costs, and the cost of goods sold that’s dependant on each sale for every kind of product. So your total costs depend on how long a game you’re playing in your financial plans. Decisions, decisions.

- How big is your target market: This one is straightforward though. How many customers are there that could buy your product? Do you have something niche on your hands, or are your going for mass appeal? The problems you solve could only exist for five companies in the world in total, but you could also be targeting every hungry student in your neighborhood. Whatever the case, find the approximate number of your potential customers.

Divide the former answer with the latter, and voila, we now have our lower limit. Yes, cost of goods sold will make this a little bit more complicated than a simple division, but let’s keep it simple. On average we can’t go lower than this or we’d, sadly, go bankrupt.

Going over some examples should make this more palpable: There are 50 or so AAA game studios in the world. So a graphics engine targeting those has to be priced around $1.000.000 like CryEngine used to do to be profitable. On the other hand, a business intelligence software targeting enterprise companies, which there are 50 thousand of them, usually charges around $20.000. At the other end of the spectrum, Netflix, which has a possible customer base of around 500 million people, could get away with charging as low as $5 a month, even though the cost of operating it is probably higher than all of them.

Before going further, obviously, if your lower limit is higher than your upper limit, well, don’t do this. Bad venture. Sad. You’d be bankrupt. Not feasible.

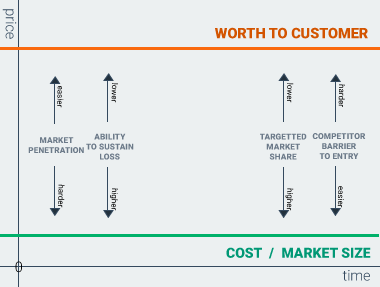

Price is a Time Function

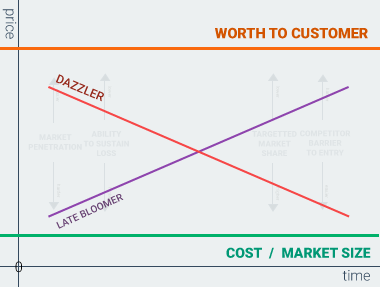

This might be unexpected, but what we’re trying to decide on is a function, not a constant. We have to be aware that price is something dynamic that is changing with time. It could and probably should differ along various phases of projected timeline for your product. So to correctly reflect this in our chart, let’s put some axes on it. Yes, those bold borders that we just outlined could change over time as well, but we’ll neglect that for the clarity of our chart.

Now finally, to chart a meaningful pricing line between these boundaries, we need to go over the factors that could affect the wanted y-axis at specific points in time.

Pricing Factors

There are many, sometimes conflicting, reasons that can guide you in directions regarding price. These might affect you differently in different phases of your product. I’m going to list four specific questions that should help you find out some of those. Depending on the circumstances of your venture and properties of your product, you’ll have to identify your situation and plot your price accordingly.

- Will the market penetration be easy? Do you have the resources to create market dominance immediately? Maybe you’ve already established necessities such as the supply-chain structure or marketing channels to get your product into the hands of your customers. If this is the case, you’ll have the opportunity to start with a steep pricing point. But maybe, customer habits are working against you, and you need brand awareness, customer trust, or even user content until you’re there. If you’re expecting hardship penetrating the market, lowering your price is one of the most effective tools in your box

- How long can you sustain a loss? How much cash you have, how much investment can you find, and how much time you have until you need to settle your debts? Lots of big players today operated at a loss (some still do) for years and survived with investments. A little loss today with a lower price point today might mean lots of revenue down the road.

- Are you a risk seeker or risk averse? Not everything is about your product; some things are about just you. How ambitious are you and how close can you get to the edge until you’re growing at a rate that satisfies you? If you want to outpace everyone by continually undercutting your opponents’ prices until they’re no more, so you’ll finally show the world that Jeff Bezos evil laugh you’ve been practising every night, why not go lower?

- How high is the barrier to entry? Some companies have some awesome trade secrets and avoidable patents. Some managed to create an impenetrable unethical monopoly, so they have some time until their competitors emerge. They are the ones that can get away with charging high prices much longer than others. But if your big successful idea was selling potato chips in a cup, and now the wolves are coming for your profits at full force, you may have to cut your prices at some point sadly.

Soit’s done! After we apply these factors, we finally have our completed pricing chart. Looks simple enough. Now, let’s give examples of two types of products or services that could follow different paths, so everything makes a little bit more sense.

Pricing Examples

Our first product is a dazzler. It’s from a company with so many resources that it was even on the evening news when it debuted. It caught the eyes of its customers who have no idea of its costs and charged a high price for a long time. Or it was something like a VR headset, which had high initial R&D costs, but its enthusiastic early adopters were willing to pay for that anyway. But over time, as its competitors emerged sniffing the money, and as its on-going costs are going down, it has gone cheaper and cheaper.

The second product is a late bloomer. This one had to start low until its value proposition reached its potential because it depends on customer-generated content. Or it could be that its business model has raised some eyebrows and they need to put some known brands in their customer portfolio to get going. Maybe it was even a free service in the early days, though at some point, everything went right and customers start flocking to it by themselves. Consequently, they raised their prices bit by bit. This could be that free club membership so hip now that you need to put some good money to get in.

Don’t be afraid to start low because of retention problems. You could always raise prices only with just your new customers as your base grows. In an exponential growth curve, they will continuously be the bulk of your total sales.

Other Factors

I know I said the chart is completed. But there are a few more important details that I’d like to mention that could help you get this right before I wrap up.

Localization

If the primary factor in your price is the worth your customers are putting in, and not your costs, almost always localise the price because that worth will fluctuate with their buying power.

Segmentation

Similarly, customers in the same locale could also have different reactions to your price based on their segments. That might be the reason Windows Ultimate and Home editions have such varying price points, even though they are more or less the same.

Don’t be afraid to change your plans

Be on the constant lookout because circumstances change. Even if they don’t, you could always try different price spikes to gauge your customer’s response. Who knows maybe you could find something that works better for you.

Wrapping up

There are other monetisation methods to go through. Also, pricing is tightly coupled with marketing, so promotions and the way you disclose your prices are relevant subjects too. But I’m feeling like we have covered the basics on this article, and I really hope this works for you as a concise introduction to the topic. Cheers!